Where does LLM-assisted software development actually help with development productivity, and where does it fall short of expectations? Rather than viewing AI in software development as a one-dimensional productivity accelerator, we explore these questions along several dimensions offered by a Stanford-affiliated study: project maturity, task complexity, and programming language popularity. The goal is to create a more realistic picture for the expectations around AI for software developers and engineering leaders alike, beyond the current hype.

Where do you even begin measuring productivity gains from using Large Language Models (LLMs) in software development? For this short analysis, I’m drawing on data from the talk Does AI Actually Boost Developer Productivity? (Stanford 100k Devs Study) by Yegor Denisov-Blanch. In the study, 136 teams from 27 countries were asked whether they see productivity improvements from using AI (more precisely: LLM-assisted software development).

The following charts are relevant to my exploration of the “what actually matters” factor. I show and interpret them here in this short article.

1. The Context Brake

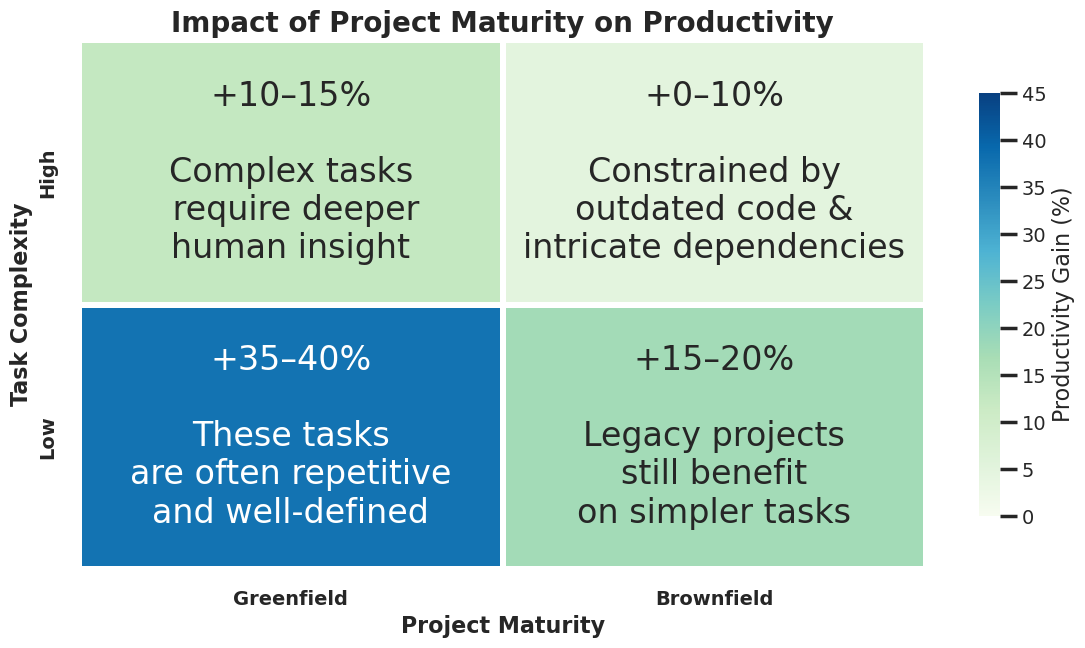

One of the most interesting findings from the talk is a 2×2 matrix that shows in which situations AI assistance actually delivers a productivity benefit for software developers. Rather than making blanket claims about AI productivity, the matrix breaks the question down along two dimensions: how mature the codebase is, and how complex the task at hand is. The results are more nuanced than the usual promises on the glossy brochures (or websites) of various AI tool vendors would suggest.

My interpretation

The matrix shows that AI productivity gains are highest in greenfield projects with low task complexity, where study participants report a 35–40% increase. The reason is obvious to me: low-complexity tasks are often repetitive and clearly defined, so AI can reliably generate boilerplate-heavy code with minimal risk of error. On top of that, I think we’re in the league of to-do list apps here: programmed a thousand times, and a thousand times nothing further came of it.

However, gains diminish significantly as project maturity increases and/or task complexity rises (i.e., once things get serious):

- In brownfield and legacy projects, gains drop to 15–20% even for simple maintenance tasks, as outdated code and intricate dependencies constrain what AI can safely contribute.

- For high-complexity tasks in systems that already resemble a Big Ball of Mud, gains shrink to just 0–10%, because the AI struggles to reason about tangled architectures, unclear implemented ideas, and deeply nested logic.

This is hardly surprising to me at this point: the underlying training data comes in large part from publicly accessible code repositories. There’s a clear bias in what gets shared: code you wouldn’t be embarrassed about in public (at least that’s how it is for me). The actual mass of code that follows other ideals remains locked away in the closed software systems of enterprises. The first encounter with this kind of code can therefore be disorienting for an LLM, making it harder to adapt familiar patterns from its training data to the existing codebase. Or as Ludwig Wittgenstein said over a hundred years ago:

The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.

But even in ideal greenfield environments, high-complexity work limits AI’s impact to 10–15%, because such tasks demand deeper human judgment that mechanical automation cannot replace. AI can assist, but it cannot yet replace the architectural thinking and contextual judgment that complex engineering and domain knowledge require. This is also related to the limited amount of available context capacity (see also my assessment in “Agentic Software Modernization: Chances and Traps”).

TL;DR: AI delivers the most when the problem is well-scoped and the codebase is clean. High task complexity and legacy code are the two primary productivity killers when using AI — especially in combination (which is likely the reality for most of us).

2. The Niche Penalty

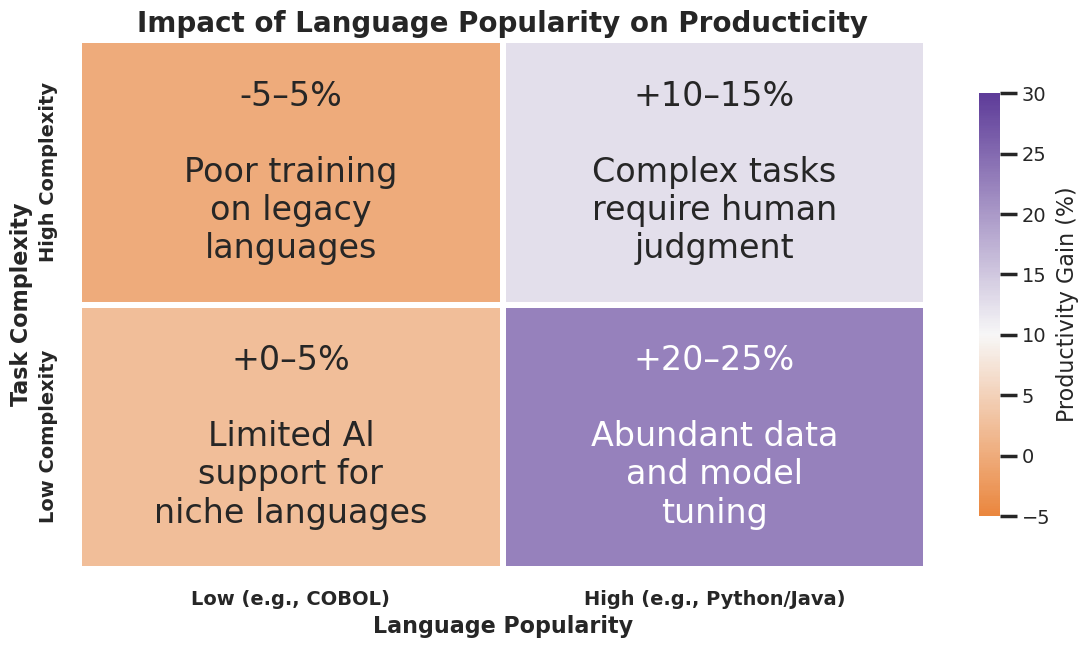

The second chart shifts the lens from project maturity to programming language choice. It turns out that the popularity of the language you work in has a substantial impact on how much an LLM can actually help, driven primarily by how much training data exists for that language.

My interpretation

In popular languages (e.g., Python, Java), LLMs deliver their highest value: productivity gains of 20–25% on simple tasks thanks to abundant training data (e.g., through Reinforcement Learning on thousands of simple question-and-answer pairs), and 10–15% on complex ones. LLMs can still provide good support here, thanks to vast amounts of diverse training data in the respective popular programming language. But even in this best case, complex tasks still require human judgment, meaning AI acts as an accelerator rather than a replacement.

Conversely, niche languages (e.g., COBOL — though that’s already mainstream to me personally) see negligible gains of 0–5% for simple work due to limited training data. For high-complexity tasks, the situation deteriorates further: productivity can actually drop to as low as -5%, as the AI enters a hallucination-prone zone where it confidently produces plausible but incorrect output. This illustrates that without sufficient training data, AI tools can become a liability rather than an asset for complex engineering work. Personally, I don’t see this changing positively in the near future either. It’s also becoming apparent that even actively soliciting code in niche programming languages doesn’t lead to acquiring decent training data (and let’s be honest: which insurance company wants to put its COBOL-written calculation engine on GitHub?).

The underlying driver across all four quadrants is the same: the more training data available for a given language and task type, the more reliably AI can contribute. Language popularity is therefore not just a matter of personal preference but a direct indicator for the more productive use of LLM-assisted software development.

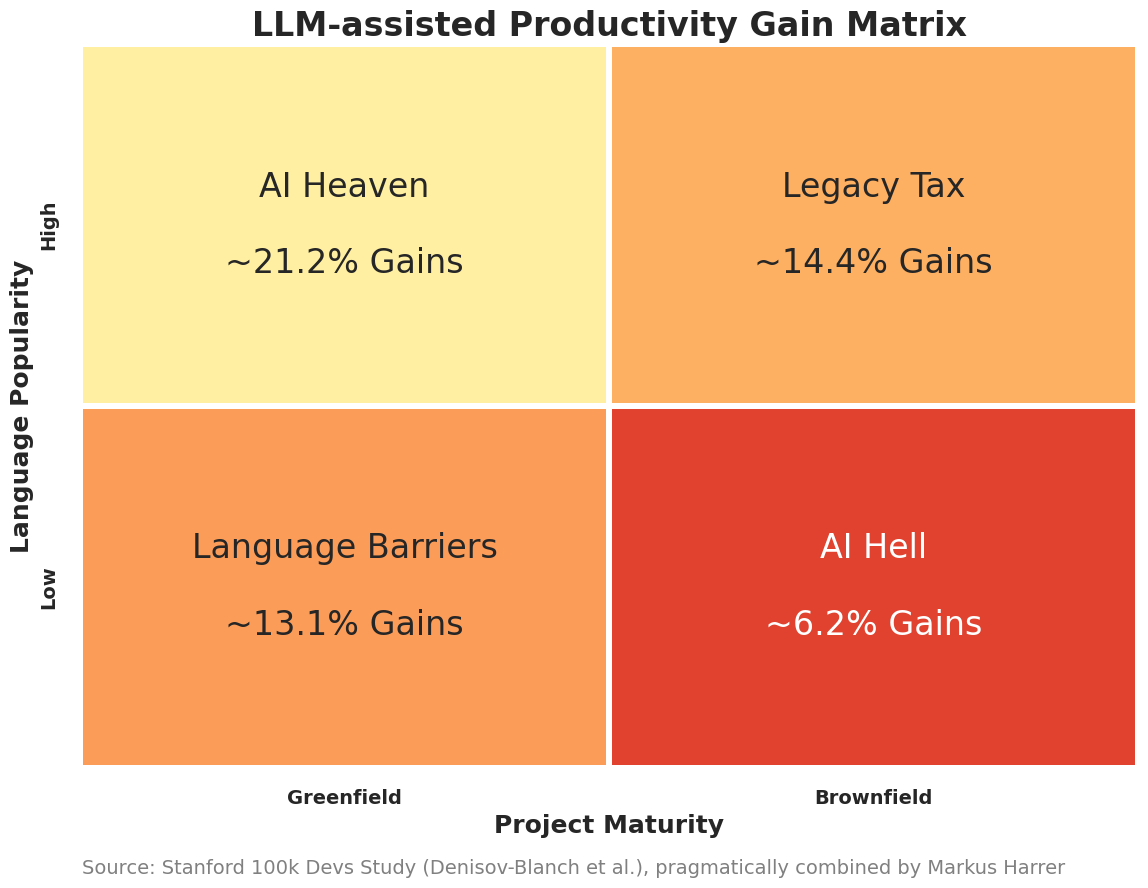

3. Heaven or Hell

For the third chart, I informally combine the mean productivity gains from the two previous 2×2 charts into a third perspective. This shows productivity gains broken down by programming language popularity and project maturity. This perspective is particularly interesting to me because I have a concrete reason for it: I’m partly involved in projects that use programming languages that don’t even make it into the top 50 of the most popular programming languages on the TIOBE Index (https://www.tiobe.com/tiobe-index/), as well as languages that will never appear there because they only exist within a single company. It goes without saying that these are decades-old, massive software systems that are now slowly wanting to be modernized.

Note: This combined view is not a formally validated model but rather a pragmatic thought experiment, blending two independent data sources through simple averaging. It is meant to provide orientation rather than serve as a precise prediction.

My interpretation

When combining both dimensions — project maturity (greenfield vs. brownfield) and programming language popularity — four interesting quadrants emerge. The best-case scenario, “AI Heaven,” occurs when working in a popular language on a greenfield project, yielding ~21.2% productivity gains. This is the ideal state: abundant training data meets a clean, unencumbered codebase. AI can operate at full potential. This is also why vibe coding and prototyping with languages like TypeScript and friends works so brilliantly.

Moving to brownfield projects in popular languages, gains drop to ~14.4%. You’re now paying the bill for letting best practices around code hygiene slide (there’s also an excellent further talk by Yegor Denisov-Blanch on this: “Can you prove AI ROI in Software Eng?”). The LLM still understands the well-known programming language well, but the complexity and technical debt of the existing codebase limit its contribution.

Interestingly, niche languages on greenfield projects still yield ~13.1% gains, only marginally lower than the legacy code scenario. This suggests that a clean codebase can partially compensate for weaker training data, but the language barrier still sets a meaningful ceiling. My prejudice here is that it’s simply always easier to start on a green field, regardless of the programming language (I still remember the days when people used to say “with Scala / F# we’re just faster,” which even back then left me cold. It gets interesting when you have a mountain of code that goes beyond a to-do list).

The worst-case scenario is “AI Hell”: a niche language combined with a brownfield codebase, producing only ~6.2% gains. Here, both obstacles compound each other. The AI lacks sufficient training data for the language and simultaneously struggles to reason about a tangled legacy codebase — the result is unreliable outputs and a high risk of doing more harm than good.

The key takeaway is that language popularity and project maturity are both independently significant, and their negative effects are additive: each dimension reduces AI productivity on its own, and facing both together pushes gains to the lowest tier. Teams working in niche languages on legacy systems should be especially cautious about over-relying on AI tooling (see for example my article “Software Analytics going crAIzy!”).

PS: Did I mention that I’m a follower of the Boring Software Manifesto and have been preaching for years that everyone should join it? I believe that in the age of agentic software modernization, the manifesto is becoming more relevant than ever before. 😉

If you are interested in the charts, here you can find the Jupyter Notebook that created the images based on the existing data from the talk.